What would you call an innovative food program that benefits schools and students? I think I’d call it “No Hungry Child Left Behind.”

The Community Eligibility Provision, or CEP for short, is just such a program. The CEP launched in the 2011-12 school year in three states—Illinois, Kentucky, and Michigan—as a way to increase school meal participation and provide no-cost breakfasts and lunches to all students. The program has grown by a few states each year, and, starting in the 2014-15 school year, became available to schools nationwide.

The CEP was enacted as part of the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010. It provides high-poverty school districts a way to offer all students no-cost meals, while at the same time reducing free- and reduced-price meal paperwork for the schools and increasing federal reimbursement dollars.

Sounds good so far, but how do you know if you qualify?

Schools can be considered individually, in groupings within a district, or as an entire district. If 40 percent of students in the school or schools considering the CEP are part of programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Temporary Assistance for Needy families (TANF), or the Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations (FDPIR), then all students in that school can be served no-cost breakfasts and lunches.

Taking the first step

Winnie Brewer, the Foodservice Director at Marion City Schools in central Ohio, says the scariest thing for most schools is jumping in on the CEP. She urges schools considering the program to “really know your budget” and analyze the projected Community Eligibility costs compared to free- and reduced-price meals. Her analysis predicted a 10 percent increase in students eating free lunches. The reality was an even better 20 percent.

“The formula is a bit confusing because there is a magic number to become 100 percent qualified,” she says. “Marion is not 100 percent qualified, but it has still been a big benefit to the district and students.”

Success at lunchtime and beyond

Marion, which prepares 4,200 meals a day for K-12 students in nine buildings, has 91 percent of its student meals reimbursed at the no-cost rate, with the remaining 9 percent at the paid rate.

Fort Wayne Community Schools in Indiana, which serves more than 7 million breakfast and lunch meals a year to 30,000 students, has seen a similar success story. The CEP is available districtwide in 45 elementary and middle schools, where breakfast participation rose 48 percent.

“Breakfast is served right at the door when students walk into the school,” says Candice Hagar, Director of Nutrition for the school district. “They can pick up their breakfast and take it right into the classroom.”

To implement this system, Hagar says the foodservice program had to change from serving breakfast in the cafeteria to making it a grab-and-go meal served right at the door.

“Under our old system, students who ate breakfast were allowed to come into the school cafeteria to sit and eat—the rest of the students had to stay on the buses until it was time to start class,” Hagar says. “With all students eating a no-cost breakfast, everyone can grab a meal, go to class, and eat.”

For Hagar, this change meant careful attention to budgeting, right down to analyzing costs such as how many more trash bags would be needed with the CEP in place.

Weighing the options

The biggest budgeting concern, of course, is determining whether it makes financial sense to shift from a free- and reduced-price meal program to the CEP reimbursement formula. Each school needs to determine what reimbursement percentage fits the budget. At the Madison Metropolitan School District in Wisconsin, that reimbursement percentage needed to be as close to 100 percent as possible.

Steve Youngbauer, the Food and Nutrition Services Director in Madison, achieved this goal by creating three groupings that utilize CEP at 18 of the district’s 61 schools. Although it’s just the first year Madison has been part of the program, the success has the district hopeful about expansion in the future—breakfast participation is up 25 percent over last school year, and lunch is up 15 percent at its CEP sites.

Big benefits for schools and families

Beyond the reimbursement calculations, districts realize CEP advantages in other ways as well. Because there are no applications to process, administrative time and effort shrinks. Plus, there are no worries about whether a family has money in its meal account.

“We don’t have to worry about whether a student has forgotten his meal money, and we don’t have to contact families to collect,” Youngbauer says. “Making those calls isn’t easy, and collecting is not a good way to foster positive relationships with families. CEP takes collecting out of the picture.”

He says it also has changed the atmosphere inside Madison’s cafeterias. Students no longer fret about explaining money matters to a cashier, and that has changed the mood during the lunch hour.

At Madison and elsewhere, CEP has improved the speed of the cafeteria line while making meal tracking more efficient. There’s no logjam of students fumbling for ID cards or trying to remember and correctly punch in account numbers at a touchscreen. At the end of the line, someone from the foodservice staff simply needs to keep a count of the meals served to apply for reimbursement.

Unexpected benefits have been a blessing to schools able to make the financial leap into CEP. The program has also been valuable for students and families, with Brewer explaining that some families in Marion save as much as $200 to $300 a month on lunch and breakfast costs.

By eliminating the free- and reduced-price program, Fort Wayne has seen another big positive.

“Community Eligibility is a big deal for a lot of families, especially those who are right on the border of qualifying for free- or reduced-price meals,” Hagar says. “It’s a big struggle for them to come up with money to feed their children. Community Eligibility takes away that struggle for families on the cusp.”

In addition to providing more nutritious meals to more students at no out-of-pocket cost, other CEP virtues are starting to emerge.

“It removes the stigma for disadvantaged students, doing for school lunches what uniforms do for clothing,” Marion’s Brewer says. “With uniforms, you don’t know who can afford Abercrombie and who can’t. With free meals, no one has to know who can afford to pay and who can’t.

“It’s one of the best anti-bullying tactics I’ve ever seen,” she says.

When it came to marketing the program, Hagar said the school used every avenue possible, from website notices, letters to parents, signage throughout the city, to making sure it was mentioned during the enrollment process. Madison’s Youngbauer said his district used similar methods.

“One of the best things about CEP is that it was available on Day 1,” he says. “No families had to fill out meal applications or wait for approval. The day the school year started, everyone could go through the line and be fed.”

Crunching the numbers

By taking the number of students eligible for SNAP and other programs and multiplying by 1.6, the

result is the percentage of meals reimbursed at the no-cost rate.

This means if 62.5 percent of students qualify, then all meals are reimbursed at the no-cost rate, because 62.5 x 1.6 = 100 percent. If the number comes in at less than 100 percent, then that number is reimbursed at the no-cost rate and the remainder is reimbursed at the paid rate.

The last word

All foodservice and nutrition teams understand that their job is to support the education process, and Marion’s Brewer notes that healthy, free meals are a great way to reduce stress on families and make classrooms function better.

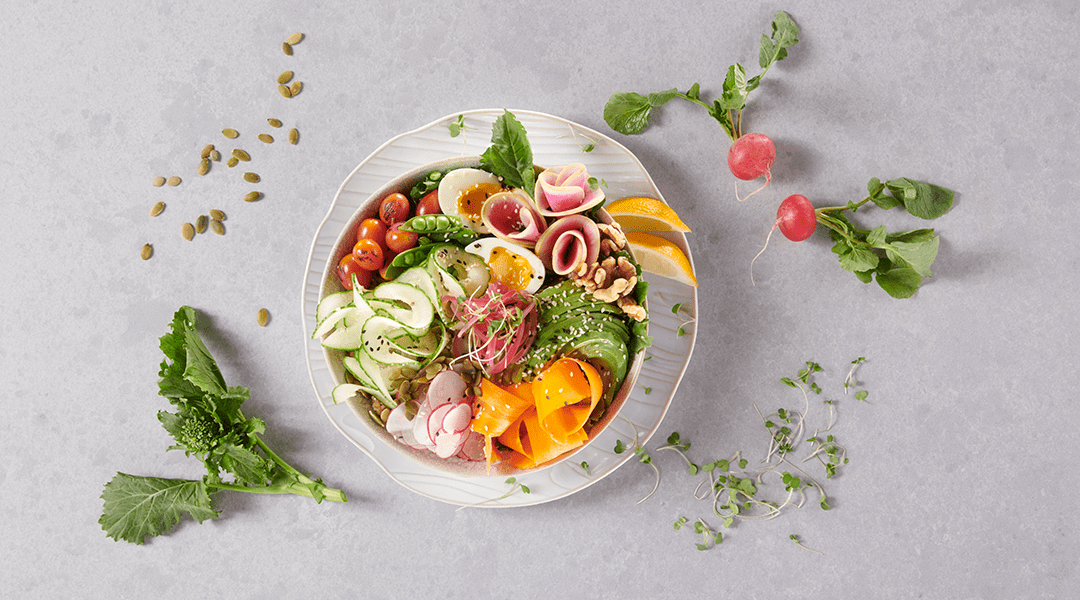

“One in four kids deals with food insecurity—they don’t know where their next meal is coming from,” she says. “Community Eligibility is a result of recognizing that need. We can feed kids two or three meals a day (breakfast, lunch, and afternoon snack) and model healthy eating through the MyPlate program. Filling this basic need is one big step toward ending childhood hunger.”