It’s summertime and the living is … busy. Students may be away on summer break, but not those who manage student dining.

Whether it’s K-12 or a college and university dining, summer is no time to rest. In between planning and ordering for the academic term ahead, foodservice directors are hustling to run summer feeding programs, camps, conferences, and a host of other activities that keep staff members hopping all summer.

Many K-12 schools pick right up the first week of summer with free or reduced-price meals through the USDA Summer Food Service Program. This is true for Terry Fuller, Foodservice Director at Peru Community Schools in central Indiana. She has a waiting list of staff members eager to work during the summer months.

“I have staff begging to work,” she says, noting that she employs two people at each of eight sites her district operates. “I’m fortunate to have workers who are in it for more than the job—the kids we feed in the summer know they’re going to see the same smiling faces they see in the school cafeteria.”

Fuller’s staff feeds an average of 500 to 800 children a day—a small percentage of the district’s 2,300-student population. But she is always looking to expand the program, reaching children in all directions. Hot meals are brought to four churches, three schools, and a YMCA building located near baseball practice fields and a summer circus camp.

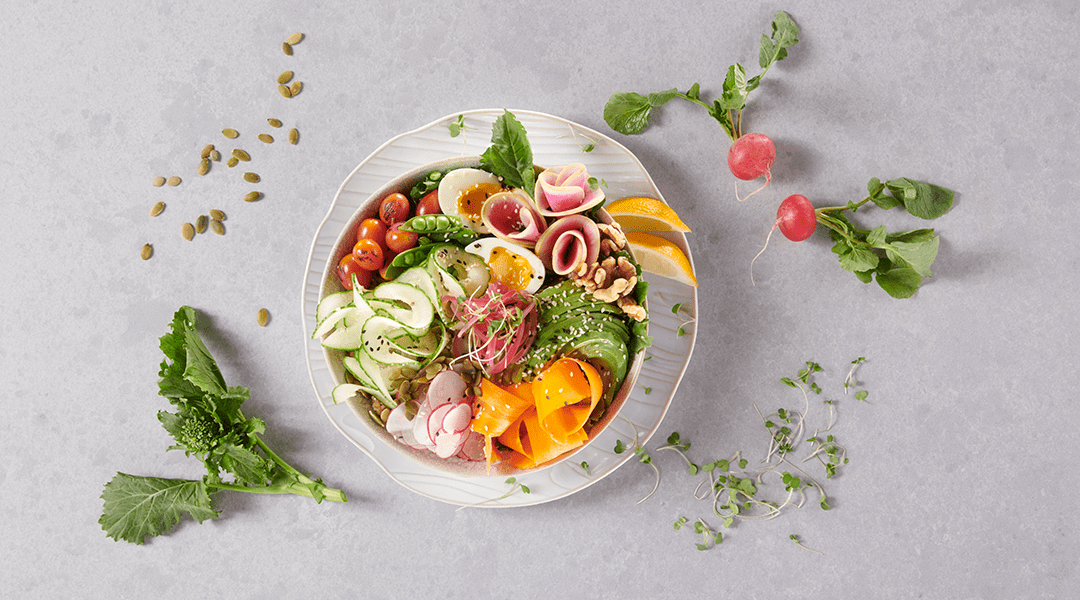

“Our service is right before or right after their practice times, and the coaches and the trainers know we’re there and the children will eat right,” she says. That food includes a cup of fruit or vegetable, one or two grains, two ounces of meat, and eight ounces of milk.

Serving Big Meals on Campus

Providing food for camp activities helps Lynn Geist, Foodservice Director at Pinellas County Schools in Florida, keeps her staff working during summer. She says her district supplies food for district students enrolled in a summer computer camp and marine biology session at the University of South Florida campus in St. Petersburg.

“I would have a staffer place the order each day for the 30 kids in the camp, and we would put the unitized meal in a delivery van and transport it,” Geist says. Meals include such items as turkey and cheese sandwiches on wheat, Italian subs, wraps, peanut butter and jelly, two servings of fruit and vegetables, and milk—all free to students under 18 and reimbursable through the USDA program.

The program was initiated after the organizer called and asked whether there was a way to feed students. After a pre-operational visit to assure safety and accessibility—the university had to require a classroom area with a countertop and a refrigerator—the program began. As for the staffing, well “nobody seems to mind driving out to the beach in summer,” Geist says.

The district also has a very active summer feeding program, providing meals at 120 sites and employing 60 people (40 at the locations and 20 in production).

“We set up at boys and girls clubs, Police Athletic League summer programs, church vacation Bible schools—places where we can attract large numbers of students,” she says.

During the school year, Pinellas feeds 57,000 lunches a day. That number drops to 7,000 during the summer. That’s why Geist said she is always talking with officials at libraries and public housing complexes about setting up summer feeding.

“We’re trying to reach out and find the other 50,000 students,” Geist says. “This summer, we hope to have 130 to 140 sites.”

Involving the Community

Finding students during the summer also is a challenge for Erin Ripley, SNS, Foodservice Director at North Adams Community Schools in Decatur, Indiana.

In 2015, her district fed students at parks, pools, libraries, camps, and school buildings, keeping 14 of her 28 staff members working during the summer.

Ripley encourages parents to join children when possible, although parents must pay for meals—$3.50 to $3.75. One event she’s especially pleased with is Summer Family Movie night at the district’s Bellmont High School.

Meals for the kids are free as part of the summer food program. Ripley has lined up sponsors—a local real-estate company and the Optimist’s Club—to pay for adult meals.

“We get 60 kids and 20 to 30 adults,” she says. “It’s a great way to bring families and the community together around the school.”

A Fast-paced Summer Slate

At the college and university level, summer programs are something entirely different, but equally dependent on summer staffing. Although the student population drops dramatically during summer, Ashland University’s dining staff remains in high gear.

“When the school year ends in May, the conference season and wedding season starts,” says Fred Geib, General Manager of Dining Operations at Ashland. “We keep at least half of our staff working most of the summer.”

The university hosts at least one major church conference each summer, caters a number of weddings at its campus chapel, as well as feeds those who attend sports and music camps, business events, and summer graduate school programs.

“Once we hit mid-June, we’re open seven days a week and provide anywhere from 1,000 meals to 20,000 meals a week,” Geib says.

One of the special events on campus is the Summer Chef Camp for 10- to 18-year-olds. It started with 25 participants the first year and grew to 70 in the second year. Geib requires all six staff chefs to be available for the two-day camp, which teaches youths food and preparation basics the first day and ends by putting those skills to practice and making meals on the second day.

“Kids see chefs and cooking programs on TV all the time, and they get to know about food,” Geib says. “This camp lets them understand more about culinary arts at the same time it showcases our dining service for people who could one day be enrolled as students.”

A parent who observed the Chef Camp made a suggestion that prompted another summer program: a weeklong Girl Scout cooking school.

“The parent of a Chef Camp attendee pointed out how the Girl Scouts were having trouble finding a way to earn their cooking badges,” Geib says. “So we set up a five-day event that involved 10 to 15 workers and one chef.”

Younger Scouts learn to bake cookies, brownies, and cakes, while older Scouts not only prepare foods, but also learn about topics such as sanitation, food safety, and meal planning.

The big, all-hands-on-deck event of Ashland’s summer is the annual Testament Conference. For the past 15 years, 2,000 attendees swarm campus for four days, consuming 4,000 meals a day.

“It’s a lot of work to make 16,000 meals over four days,” Geib says. “But after all these years, it’s like a visit with old friends—we enjoy seeing them and they enjoy catching up with us.”

Setting up Shop

Lynn Geist offers advice for K-12 districts looking to start summer programs.

- Establish connections with people who do K-12 outreach. Don’t overlook university programs

- Visit them and bring information on summer programs. Bring information on what you can and cannot do

- Get permission to be on site

- Have a place to set up, as well as a rain site

- Have a place to dispose of trash

- Explain that food safety is your responsibility, and that you will provide necessary training or expertise

- Make a pre-operational visit and determine the estimated time of meals—Plan about 20 meals per labor hour, with a service time of two hours

- Make sure everyone in the chain of command OKs the program

- Be prepared to do the marketing, communications, and signage.

- Consider seeing grants through the Department of Education, Department of Agriculture, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, W.K. Kellogg Foundation