Wide-open dance floors are great for dancing, but terrible for serving food. Economy of space is key to a successful foodservice operation. Nowhere is this more true than in K-12 dining, where appearance and efficient service play a big role in participation, nutrition and satisfaction.

Don’t waltz around making one physical change after another without keeping data and efficiency in mind. This advice comes from Scott Reitano, Principal of the Indianapolis-based Reitano Design Group, which designs kitchen and serving areas for schools, colleges and universities, hospitals and healthcare communities nationwide.

Whether you hire a professional designer or plan to make changes in the dining area yourself, he suggests looking at all the data through this lens: “It’s about the food and the people eating it.”

Thinking outside the lunch tray

The power of food cannot be denied. At least three times a day, food is front and center in people’s lives. At every party or social gathering, friends meet around the food table. School foodservice has much to learn from this, Reitano says.

He points to hospitality—treating students as guests at an event—as a way to encourage better eating. Today’s students are not traditional, and their food experience isn’t either. They no longer expect to start at the beginning of the lunch line with an empty five-compartment tray and emerge at the end with a full tray.

“Today we want kids to eat better, healthier foods,” Reitano says. “But if we don’t change the way we’re serving it to them, the change is either not going to happen or it’s going to be a lot harder.”

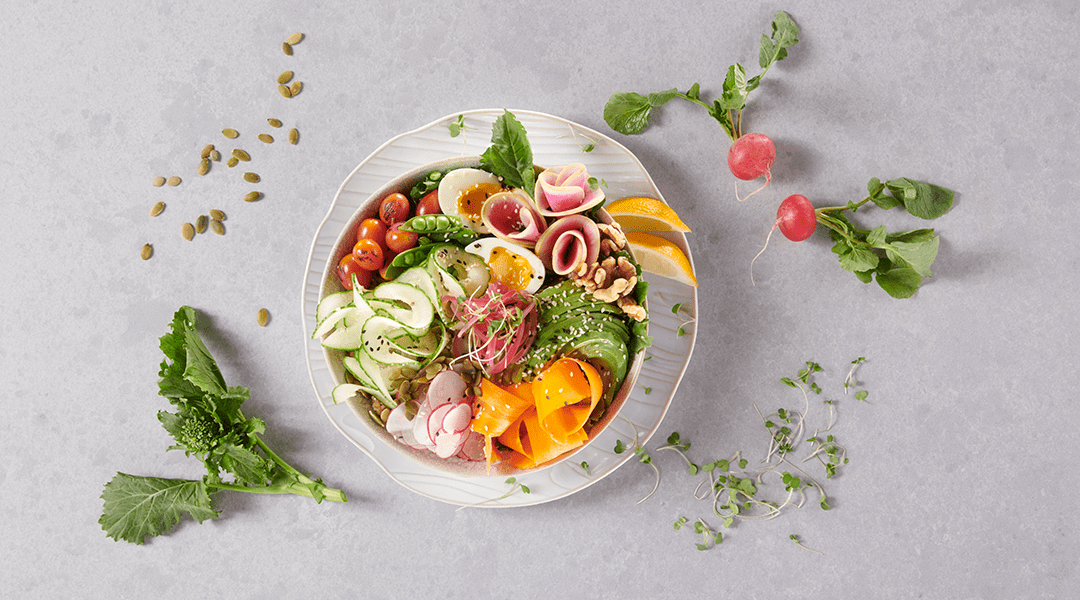

Taking a page from the buffet-line approach, try putting fruits and vegetables out front as the first choice. When the plate gets mostly filled with the first few healthier items, there’s less room for other choices. “Let’s get really crazy and make fruits appealing,” Reitano urges. “Studies have shown that when we peel oranges and slice apples, consumption goes up more than 70 percent.”

You don’t need food police

Encouraging students to choose healthier options promotes better eating without looking like the food police. It’s all about doing a better job of marketing food. By using data found in three areas—context, benchmarking and trends—Reitano says schools can design in ways that drive efficiency, participation and sales.

Context. Every foodservice program has a story, so take a look at yours. Are you a rural or urban school? Do you have a large immigrant population? What’s the ratio of free and reduced-priced lunches? Are students leaving campus to eat or packing lunch most days?

Your story is a form of data, Reitano says. Only when you know answers to questions like these can you make informed changes. Fish may not be as popular in a rural community. Asian choices may not resonate in a district with a growing Hispanic student body. And so it goes.

This rough data can spur new concepts. “You may learn students want more customizable options, like at a fast-casual restaurant,” Reitano notes. “If you give them more choices, participation goes up and food waste goes down. This kind of data is significant.”

Benchmarking. Some data comes in the form of numbers, and Reitano reminds foodservice directors that numbers don’t lie. Day-to-day participation rates should inform menu planning. Those numbers are no-brainers for every foodservice director.

Finding other numbers calls for digging deeper. Use every number as a measurement to set expectations about what can be accomplished with your space and budget. Compare square footage with other area schools. You may discover you have an opportunity for a retail café with extended hours to better serve your student body. “Everyone wants to know what other people are doing, but you should only do it if the numbers make sense,” he says. “Do a spreadsheet—if their school has 2,500 students and yours is only 1,000, you need to scale numbers to evaluate the potential.”

Food waste is another valuable measurement, Reitano says. “Part of food waste is not overproducing food. If you put a bucket in the kitchen and weigh the unserved and uneaten food at the end of the day, you can track it and make changes that go directly to the bottom line.”

Trends. Young people are shaped by trends. Fresh, customizable, socialization, healthy, sustainable—these are some of the buzzwords in student dining. Each one of these trends is something school foodservice can address.

A deli-style, fast-casual (think Chipotle) or grab-and-go setup speaks to students seeking freshness and customization. “Fresh matters. If you see a panini sandwich or a burrito made right in front of you, there’s a perception of freshness,” Reitano explains. “When I see the back of the house coming to the front of the house it equates to engaged eating.”

It’s a great way to increase satisfaction and reduce waste. Instead of putting food on a plate that gets thrown away, offering the ability to choose increases the likelihood of consumption.

Three simple words

The secret to understanding data and creating effective design changes can be summed up in three words: “follow the food.”

Efficiency starts when the food comes in the back door. The coolers should be close by to preserve freshness and minimize stocking time. It should be a pretty direct trip from the cooler or storage area to the prep station to minimize steps. The place where it’s most important to watch for efficiency is the distance from the cooking area to the serving area.

“Food quality starts to diminish the moment it comes out of the oven, so don’t make the distance between cooking and serving something that leads to lower quality.”

Paying attention to kitchen flow makes it possible to do something in two steps instead of five. It may not sound like a lot, but it’s the kind of change that adds up to meaningful savings over time.

Attention to efficiency also matters in the K-12 dining room. Saving a few steps to the salad bar makes it easier to keep refreshed, which enhances appearance and increases sales a little bit each day. Better traffic flow for staff and students, combined with attractive presentation results in quicker service and more sales per labor hour.

Here’s to a More Appealing Orange

Don’t blame the rules, blame the thinking. Kitchen and foodservice design expert Scott Reitano knows it’s hard to meet National School Lunch Program rules and grow student participation.

For example, if the rules call for serving half an orange, but children aren’t eating the orange, it doesn’t mean the rule is bad. Instead, he considers it a challenge that design thinking can solve.

For inspiration, he listened to his wife. As a second-grade aide, she knew every time oranges were served. “Every child either asked her to peel the orange or did not eat the orange at all,” he says.

Peeling and sectioning the orange, he notes, makes it easy for everyone to eat healthier. “It’s our job as designers to see better ways to bring people and food together.”