Hunger doesn’t take a summer break. When the final bell rings to end the school year, schools with large free- and reduced-price meal populations become part of the hunger safety net. They operate summer food programs that serve thousands of free breakfasts and lunches to children under 18. While the meals are free to students, there’s a cost for schools that offer them. Managing that cost requires attention to data and operational best practices.

School districts where greater than 50 percent of students receive free or reduced-price meals are eligible to participate in the Summer Food Service Program (SFSP). These schools are reimbursed for the cost of meals by United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), which oversees the program. Unless a school district secures grant money or creates a partnership with another organization, those reimbursement dollars must cover administrative, labor, transportation and other operational costs.

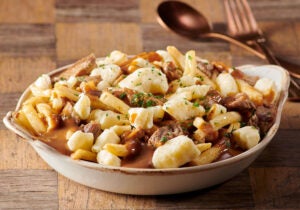

Build freshness into a simple cycle menu

At Marietta City Schools north of Atlanta, Foodservice Director Cindy Kanarek-Culver relies on data to run two school serving sites that also operate as prep centers for 40 other summer food locations countywide. With a staff of 20, Marietta provides 2,000 meals a day during the summer.

“I use data to tell me what foods young people like, and then I create a one-week cycle menu instead of a two-week menu,” she says. That helps her limit the variety of food she must have on hand to create cold meals on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays and hot meals on Tuesdays and Thursdays. Because she’s serving foods she knows students enjoy and since youngsters don’t come for a meal every day, the repetition doesn’t have a negative impact on meal count.

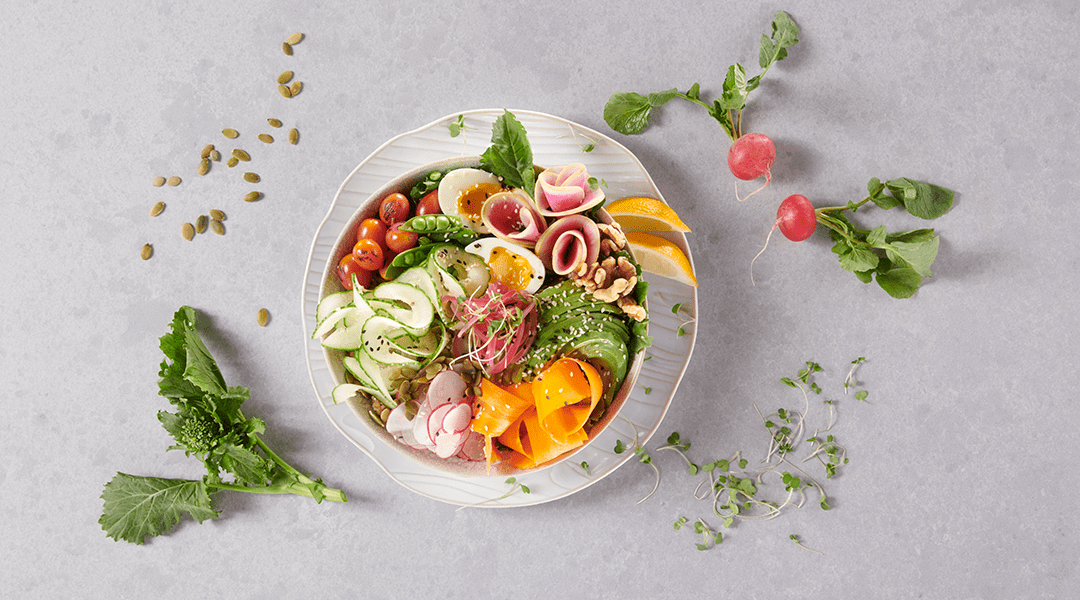

After a few years of running the summer program, Kanarek-Culver has collected enough data about food amounts needed to budget some of her federal allotment on summer produce.

“Our goal is to make sure children have the same opportunity to get fresh food during the summer as during the school year, so we reserve some of our dollars to buy fresh produce,” she says.

Consider the costs of pickup vs. delivery

Marietta also reduces food costs by requiring the 40 non-school sites to pick up food at the prep locations. This requires Marietta to train someone from the off-site locations in regulatory feeding requirements and food-handling practices, but it’s a big money-saver when it comes to administrative, labor and transportation costs.

The participating camps, community centers, churches and YMCA sites are each provided a food thermometer, shown how to use it, and provided food logs to track distribution. The district uses insulated totes to keep foods at safe temperatures. It’s a setup the off-site locations have come to appreciate.

“We’ve had partners switch to programs that deliver food, but they come back when they find out other sources freeze the meals before sending them out to the sites,” Kanarek-Culver says. “We’re able to provide freshness and variety that’s very successful.”

Cabarrus County Schools near Charlotte, North Carolina, also utilizes food pickup for some of the 42 sites it serves, but it also has a mobile food bus that has helped the program grow to nearly 70,000 meals a summer. Data helps School Nutrition Program Director Daughn Baker manage the growth.

“We track everything on spreadsheets, counting the number of meals recorded by each site manager,” Baker says. “We look at those numbers when someone wants to be part of the program, and we can put together a pretty good guestimate based on a similar-sized site.”

Let participation numbers determine staffing

Staffing is another area where schools look to data for cost management. At Grand Rapids Public Schools in Michigan, Nutrition Center Supervisor Jennifer Laninga oversees 16 school sites and 16 non-school sites each summer. She has used participation data recorded over the past 10 years to determine the number of foodservice staffers she needs.

“We serve one-third of the number of meals in the summer compared to the academic year,” she says. “And since we only staff the 16 school sites where hot breakfasts and lunches are served, I can do the work with a staff of about 35—during the school year we have about 200 employees.”

Staffing is one of the hurdles that the non-school feeding sites must address. Laninga says everyone wants to make sure hungry students get fed, but they’re not prepared for the administrative time that comes with it.

At Cabarrus, School Nutrition Supervisor Carrie Bostic says she hires a current manager to be the summer program manager at the central cafeteria. This manager handles all of the administrative paperwork, and that allows Bostic to hire 20-30 employees to manage a kitchen that produces food for all but a couple of summer reading camps and school-specific programs.

Don’t be afraid to ask for help

Data is an important tool in directing summer meal programs, and the USDA has a number of mapping and calculator tools available on its website to help with decision-making. Choosing where to locate a food program and how to calculate costs, reimbursement rates and other financial factors are keys to the success of any program.

Asking for help at the state level also is a great place to start, Laninga advises. Every state can have its own rules on summer food programs, so contacting state administrators can help avoid unexpected costs related to regulations and administration.

Getting buy-in at the district level and looking for unique ways to spread the word also can pave the way for success, Bostic says. Posting flyers around the community, sending out information with students before the end of the year, and even getting teachers to remind students can increase participation. And the summer program can even benefit meal participation during the academic year.

“We feed breakfast and lunch during summer kindergarten registration day, which falls under the summer food program.” Bostic says. “When students and parents are there together for a practice school day, they can see how good the food is and it gets the kids excited about eating at the cafeteria.”