Today’s college dining programs offer greater quality and diversity of food selections than ever before. Yet some college students aren’t getting enough to eat on a consistent basis.

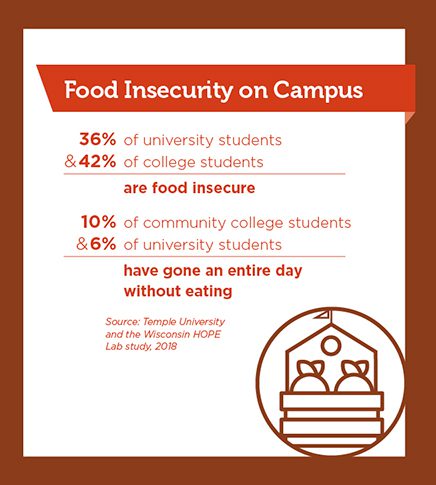

That’s the conclusion of a 2018 survey conducted by researchers at Temple University and the Wisconsin HOPE Lab. Based on responses from 43,000 students at 66 colleges and universities, the study found that 36 percent of university students and 42 percent of community college students were “food insecure” in the 30 days preceding the survey.

Food insecurity was defined as “the limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods, or the ability to acquire such foods in a socially acceptable manner.”

Researchers went on to say that “the most extreme form of food insecurity is often accompanied by physiological sensations of hunger”—sensations no doubt experienced by the nearly 1 in 10 community college students and 6 percent of university students that went an entire day without eating in the past month.

Researchers went on to say that “the most extreme form of food insecurity is often accompanied by physiological sensations of hunger”—sensations no doubt experienced by the nearly 1 in 10 community college students and 6 percent of university students that went an entire day without eating in the past month.

While HOPE Lab has been studying food insecurity among America’s undergraduates since 2008, the issue hasn’t been given much attention until relatively recently.

Rachel Sumekh, Founder and CEO of the college-focused non-profit organization Swipe Out Hunger, told the Washington Post in 2018 that, “Not a single university administrator wanted to acknowledge this was an issue five years ago.”

The HOPE Lab research helped change that, as have other recent surveys conducted by colleges—including a 2015 University of Michigan study that found that 41.5 percent of its students suffered food insecurity.

Students lead the way at the University of Michigan

Steve Mangan, Senior Director of Michigan Dining, says Michigan students were aware of the problem and proactive in addressing it even before that study was published.

“About five years ago, students founded Maize & Blue Cupboard to distribute free food to other students in need. It’s a once-a-month distribution program that just became bigger and bigger, to the point that students were lined out to the road on distribution days.”

In addition, The Student Food Co. has been distributing fresh food twice monthly at cost to students, and Food Recovery Network student volunteers have been gleaning Dining operation leftovers and taking them to the local food bank.

In 2017, Central Student Government leadership approached Dining with a request to trade meal swipes for meals that would be given to those without. “I asked them to go back and look for ideas that don’t change the financial equilibrium in Dining while looking for deeper solutions to the issue,” says Managan. “Simply providing meals doesn’t address the root cause of the problem.”

That led to the Central Student Government funding emergency meals that are managed through the Dean of Students office, in a way that compensates Dining for them. Perhaps more importantly, it led to the establishment of a working group that has, for the past year, explored solutions that would involve students and many different university departments.

After all, Mangan says, the factors underlying campus hunger are complex and multifaceted. “Some students find that their financial aid isn’t enough to cover all their expenses. Others may be on their own for the first time and have no idea how to budget and shop for food. They may not be able to cook. They may have social and interactional issues that contribute to their food insecurity. So a more holistic approach is required.”

Opening a daily food pantry

Alex Bryan, Manager of Michigan’s Sustainable Food Program, has teamed with students to develop one such approach. “Dining had space available in the form of an abandoned kitchen in the basement of a residential hall,” Bryan says. “We retrofit the space and are opening a permanent, on-campus food pantry soon.”

The pantry will be stocked with a variety of food products, with an emphasis on fresh, healthy produce, dairy and other offerings. Michigan Dining is reaching out to distributors and vendors for assistance keeping the shelves lined.

“We’re looking for donations to supplement what we get from Food Gatherers, a regional food bank, and from our own backyard at the Campus Farm,” Mangan says.

A long-term solution

Food pantries are becoming increasingly common on college campuses, but Michigan’s will serve as more than just a distribution site. “We found that many food pantries provide a short-term answer to a long-term need,” Bryan says. “We’re partnering with our School of Public Health to offer nutrition education, cooking classes and budgeting help. We have pots, pans and other cookware available. We’re even printing recipe cards with ideas for the items we have in stock at any given time—like winter squash, for example.”

Other departments involved include financial aid, counseling and psychological services, wellness, student government and research. “Every department has a piece of it,” Mangan says. “That’s what distinguishes this from a typical pantry. It’s not just about food, it’s also all the other issues surrounding this basic need.”

“We’re building an entire community around this,” Bryan adds. “A diet of ramen and Wonder Bread used to be seen as a rite of passage for college students. Now there’s a realization that poor diets can seriously impact academic performance. Departments across campus see this and are joining with us to address food insecurity in a meaningful way.”

“That includes chipping in to help fund it,” Mangan says. This is funded separately from our meal plans, and it’s designed to be cost-neutral.”

No matter where the funding comes from, it’s students that are driving the program, from identifying solutions to staffing the pantry to spreading the word. “Students get it,” Bryan says. “When they hear about this, the response is always, ‘Great! How can we help?’”

Students are helping develop a food insecurity website, establish a social media presence and produce communications for use throughout campus departments. “It’s a real partnership,” Mangan says. “It’s students talking to each other and to faculty and administration to make something happen.”

What Colleges & Universities Can Do

Food insecurity recommendations from the Wisconsin HOPE LAB:

- Collect evidence to understand the problem. Knowing approximately how many students need support on your campus is critical to addressing the issue.

- Organize to take action. Leadership, often formalized by a guiding committee or task force, is an effective approach to formulating an institution’s response.

- Design programs to proactively support students. Map existing campus resources to identify what resources exist, and which are missing.

- Partner to grow and develop programs to serve students. Work with community agencies and programs as well as partners on campus.

For further details, download the “Still Hungry and Homeless in College” policy report.